The Smell of Jasmine, the Calm of the Crowd

from Essays

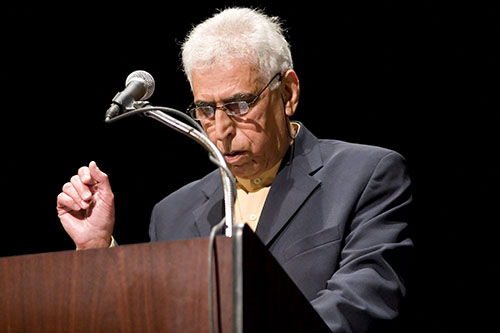

Remarks on Poetry and Politics

Cairo University

Cairo, Egypt

March 30, 2013

Do you know what a jasmine flower looks like? If you close your eyes, can you see it? Can you smell it?

It is the ancient smell of calm. The cool beauty of the night. You know the jasmine flower only opens after dark, when the sun sets and the temperature drops. The small white flowers look like the stars painted on the ceilings of the tombs of pharaohs.

The ancients knew the power of jasmine. The name is Persian. It means “a gift from God.” The Persians, the Greeks, the Egyptians all knew it had healing properties.

In fact, recent laboratory tests have found that the sweet smell of jasmine has the power to calm mice when their cages are filled with it. They stop their chaos—running, squealing, fighting—and they lie down together quietly in a corner.

Studies show that inhaling the molecules of jasmine oil transmits messages to the limbic system of the brain, the area involved in controlling emotions.

Have you seen jasmine flowers picked for oil? I was able to visit a place last year in upper Egypt where this is done. The flowers are gathered at night when the odor is strongest. Workers must pick the flowers carefully because they are so delicate. They are laid out on cotton cloths soaked in olive oil for several days and then extracted, leaving the true jasmine essence. More than five million flowers must be gathered to produce one kilo of what is known as “pure jasmine absolute.” The power of jasmine is as strong as it is rare.

I have been thinking a lot about jasmine lately.

This week, many students were killed at the university in Damascus, which is the City of Jasmine.

This week, I have talked to many mothers fearful for their children in these troubled times. Jasmine is the flower of motherhood.

And this week, I was reading the poems of your fellow student at this great university, Mohammed al-Ajami. As you know, al-Ajami is in prison in Qatar, his home country. He is in prison for writing a poem called “Tunisian Jasmine.” Last month, his life sentence was reduced to 15 years.

15 years for a flower. 15 years for a human life as delicate as a flower. 15 years for poetry, the flowers of language, the intense fragrance of words.

I want to talk today very briefly about words and their power.

I want to talk about the strange bedfellows that poetry and politics make. They are most definitely relatives. But their relations are what we might call in the United States “a dysfunctional family.”

Just two weeks ago, the third Cairo International Poetry Encounter was held. I was not there, but there were speeches and readings and debates and boycotts. There was the timeless distrust of different generations, the debates over the value of what is treasured and well known versus what is new and strange. In many ways much of what I read about the “encounter” seemed less about politics and poetry than about the politics of poetry.

I was particularly struck by the comments of one poet, Mahmoud Kourani who said that the committee that planned the encounter “is living outside history.”

Imagine that for a moment. Who lives outside history? Such a profound and provocative question. But even if we were to accept that some people are largely spectators to dramatic political events, far from protests or Tahrir, are they really outsiders? Who decides inside and out?

The poet Andrew Joron wrote an essay called “The Emergency of Poetry,” which is a play on the title of a famous poem by the great American poet, Frank O’Hara, “Meditations in an Emergency.” O’Hara wrote that poem in 1954. There was no political emergency in his life in America, in New York in 1954. In fact, he tells us in the poem that there is only the emergency of his eyes being the wrong color, that he is bored, that he is full of erotic possibility.

But are these not emergencies?

Perhaps the most famous lines in O’Hara’s poem are: “I am the least difficult of men. All I want is boundless love.

That sounds exactly like most poets I know: I am perfectly reasonable. I only demand everything. Right now.

In his essay about poetry and emergency, Joron asks a question that always gets asked—what good is poetry in a time like this? He rehearses two arguments—that poetry is politically useless, so it is free. Or that poetry can expose ideologies and speak truth to power, give a voice to the powerless and be a call to action, to counsel and console.

And then, of course, he discusses all the arguments about this. Why is that kind of language “poetry?” Is it really any different from a good speech?

When Barak Obama was first running for President, his eloquence was striking to many people. But it also made some people wary.

Another American poetry critic, David Orr, tells a story about one particular campaign event where this skepticism came out. There was a union boss in Ohio, an advocate for factory workers who supported Hillary Clinton instead of Barack Obama. At a campaign rally he criticized our future president, "Give me a break! I’ve got news for all the latte-drinking, Prius-driving, Birkenstock-wearing, trust fund babies crowding in to hear him speak! This guy won’t last a round against the Republican attack machine.”

And here’s the point: “He’s a poet, not a fighter!”

As Orr explains, there are two assumptions here: Poetry is passive and spoiled, out of touch and doesn’t know how to fight or get things done. Politics is active, messy, aggressive. It’s a fight. It’s like war. And yet, those assumptions always seem to get confused.

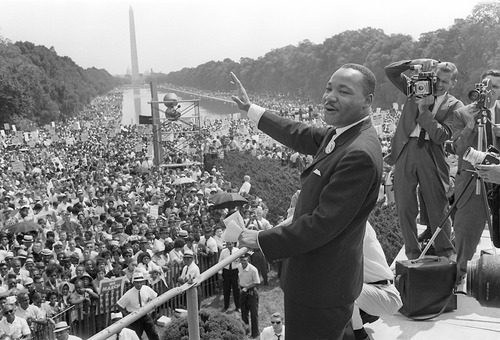

Even politicians speak about how great moments in public life are great because they are “poetic”: the Gettysburg Address, Martin Luther King’s "I have a dream” speech. And of course, at other times, like that union official, they dismiss poetry as frivolous, the words of the weak.

Both politics and poetry are actually all about talk. Think of how much political talk you hear in this country! It’s tempting to think that this dependence on works makes poetry and politics quite alike. Both are about rhetoric and persuasion and both make people listen carefully to hidden means, to subtleties. And both live in the life of the mind more than the life of the body. Or do they?

It is, of course, bodies that are summoned to the authorities. Bodies that face tear gas. And it is poet Mohammed Al-Ajami’s body that is in prison.

David Orr reminds us in his essay about poetry and politics that in the English literary tradition, two poets stand out for their engagement in the debate about poetry and politics: the romantic Percy Shelley and the wry W.H. Auden.

Shelley famously said that poets are “the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which the future casts upon the present … Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.”

And then Orr quotes Auden, but a lesser-known passage: “All poets adore explosions, thunderstorms, tornadoes, conflagrations, ruins, scenes of spectacular carnage. The poetic imagination is not at all a desirable quality in a statesman. In a war or revolution, a poet may do very well as a guerrilla fighter or a spy, but it is unlikely that he will make a good regular soldier, or, in peacetime, a conscientious member of a parliamentary committee.”

But as David Orr explains, Auden is actually agreeing with Shelley on something fundamental: both seem to think that poetic thinking is apocalyptic thinking, that poetry thinks big and urgently, about dramatic change, about absolutes, about utopias and possibilities for grandeur or despair. Poetry is not comfortable with the ordinary.

Of course, Shelley thinks this tendency is thrilling: it’s good, it’s something we should trust about the creative imagination, it’s something we should demand. I think I hear Shelley in Mahmoud Kourani demand that poets live in history, that they make history.

Auden is much more wary. He’d like poetry to be comfortable in the ordinary, to be accepting, to be quieter, to be observant, to be interested in weakness. To express Frank O'Hara’s kind of emergency: the need for boundless love.

But both Shelley and Auden believe that throughout history, the poetic impulse has tended to be grand, romantic, apocalyptic, dramatic, making large claims about how the world is or should be. Both believe that this is essentially how poetry works.

And this is how poetry can be like politics, when we think of politics as something more than legislating, as something about a vision. Every kind of politics—absolute, revolutionary, or just routine and legislative—has a vision behind it, a set of beliefs—“I have a dream!”—that rallies its supporters. And every politics, revolutionary or conservative, has its poets, poets who mirror the values of their community.

But here is where the complication comes in, here is where the family relation between poetry and politics becomes dysfunctional. And here is where we find that it’s often so difficult for different families, with different politics and poetries, to understand one another.

In America, the poetry that I write, the kind of poetry that most people write is lyric poetry, poetry that has heard Auden’s skepticism about grand claims and large voices. The lyric poem turns inward, it tries to create an entire world out of the inner life of the poet, a solitary, meditative voice, a voice of solitude, a voice of escape, a voice that resists the loudness of the world. It is a voice that David Orr wonderfully describes as “insisting on privacy.”

How has this happened to American poetry?

Orr thinks it has something to do with the individualism inherent in the habits of democracy. He quotes the famous French student of the early American experiment in democracy, Alexis de Tocqueville. Tocqueville was very wary of ways democracy can weaken communities, fray our connections to the past: “Not only does democracy make every man forget his ancestors, but it hides his descendants, and separates his contemporaries from him; it throws him back forever upon himself alone, and threatens in the end to confine him entirely within the solitude of his own heart.”

In truth, that does sound a lot like America at our worst, and a lot like poets I know. We feel alone, alone in the crowd of confusions and ambivalence that make up modern life in a wealthy consumer society. And it sounds a lot like what frustrates Mahmoud Kourani about writers “living outside history.”

If it is true, if our lyric poetry is in some important ways a function of centuries of individualism, if poets turn inward and seemingly away from politics, then why, Orr asks, does this very poetry constantly seem to insist on itself, insisting on the poet’s right to some privacy, to some alternatives from overwhelming noise, vulgarity and boredom? If we are insisting, we must be insisting to someone, unless we are only talking to ourselves.

And that creates a struggle for American poets, because we wonder whether we really have an audience. We expect people to read us privately rather than to hear us publically. We do not have a moment of revolution where people gather to hear poetry to give them the strength for the fight of politics. We reach one person at a time.

Are we irrelevant, powerless? Where is the American jasmine?

The struggle to get out of ourselves, to be engaged in something larger—the struggle for community, the struggle to be inside history—that’s one of the great struggles of American culture, of the American soul.

Perhaps, this is the opposite of the soul of the poet in revolution.

Even if we Americans can have the desire of Shelley in our bones, we live in the politics of Auden, a politics not in upheaval. True, it is a politics that is often angry and divisive, but it is one that exists more in stale legislative stand-off than in the urgent sounds of change, danger, life in the street.

It seems to me, though, that there is a place for art, a place for poetry that can be found in the meeting of these different souls. If we need to turn up the volume and break in to the solitude of the American soul, does it also make sense for artists in times of revolution to turn down the volume, to see also the solitude? To find something at least acceptable about moments stolen away to breathe in quiet, outside history?

I can’t answer that. I even propose it as a question with great hesitation. I am not living the revolution you are living.

But what I do know is that all of our poems—yours and mine—will take on lives, or not, without us. The political poem may later be read as a love poem. The love poem transformed into a political emergency.

Andrew Joron, whom I spoke of earlier, said that poetry in times of emergency is probably not the poem of anger or solitude, but the poetry of lament.

“The lament, no less than anger, refuses to accept the fact of suffering. But while anger has some urgent reason, something right now to cause it –He says the lament has a universal cause, and rises undiminished through millennia of cultural mediation. Unlike anger, the lament survives translation into silence, into ruins.”

I’d like to end with two poems—old and new, Western and Arab—to look at two forms of lament, that might express he possibility of a meeting of minds, a space where different kinds of poetic souls understand and accept one another.

First, the famous English sonnet by Wordsworth, who warns against the danger of the materialist, self-absorbed soul that is too content in the world as we find it:

THE world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers:

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

The Sea that bares her bosom to the moon;

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers;

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not.–Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathed horn.

Wordsworth offers, in the beauty of this lament, poetry as a modest alterative to “getting and spending.”

I think this rhymes with another lament for and of the present moment, a lament that is formed in the question and hopeful definition of poetry that we can find in an excerpt from Saadi Youssef’s Nostalgia, My Enemy:

Is poetry merely a reading of life?

I believe it is deeper and more vast than that.

Humans have numerous ways of reading their life, including science and politics.

But poetry is a different matter.

If science and political struggle promise and prepare for another time, poetry is current, direct and immediate. I mean that poetry’s ability to read, participate, and change is more effective and deeper in the veins.

Poetry is transformative.

On the street, in our hearts, quiet or loud, urgent or anxious, populist or solitary, on this much we can agree: our lives must be transformed. That is what good poetry does, what all good art does. And, in fact, it is a pretty good definition of what politics should be: a way to transform our lives.

So here we are in the dysfunctional family where both are necessary, both are related, both so often at odds, so full of heat and anger. Perhaps what we need is some jasmine, some cool weather, the darkness and stars, a sweet scent that can make us remember what’s beautiful, that magically, even in emergencies, can make us calm.