Traveling by Caravan

from Essays

Remarks to American Fulbright Students in the Mideast

at the Fulbright Mideast Enrichment Seminar

Rabat, Morocco,

Monday, March 12th, 2012

Thank you for that brilliant morning of presentations and discussion. I’m always so inspired by the serious scholarship, the passionate commitment to teaching, and the generous spirit of friendship that I find every time I’m with a group of Fulbrighters.

It’s such pleasure to be visiting Morocco again.

A lot of foreign dignitaries have been here recently. Secretary Clinton was just here. I’m not sure whether you heard, but Morocco actually had a visitor from Mars in July. From a meteor. It was a long trip. The meteor left Mars about a million years ago and floated around the galaxy before crashing to Earth at Tissint. Nomads saw the fireball and heard sonic booms–of a fairly tiny meteor.

Only 61 meteors have come from Mars in modern times. And this was the first one anyone seems to have seen coming.

After arriving in Tissint, then the meteorite really got busy. The biggest chunk went to Paris then to New York (where it biked around Manhattan in someone’s backpack) then finally it was flown to London.

It almost sounds as complicated as the itineraries some of you took to get here.

Now that you ARE here, I wanted to bring up what may sound like a very impatient, New York question? So what’s next?!

Actually, Jim Miller asked me to talk to you about that. He also asked me to implore you not to go to law school. But I’ll get to that in a minute.

It’s strange, isn’t it, that you’re in the middle of some of the most extraordinary experiences of your lives, and yet it’s difficult not to think about where you’re going next.

It’s what we do.

It’s the extraordinary thing about being human: we don’t really spend much time looking at the world the way it is; we actually see the world as it isn’t.

We remember the past; we imagine the future. We imagine things being different.

We’re always planning and dreaming and getting ready. So what is next?

Well, if I can really offer my profoundest hope for you, it’s that the plans you have will get messed up! Of course, you won’t need my help with that. Life never turns out how we expect it to. There are surprises. And we even make mistakes. Which is good. It’s essential. And perhaps for over-achievers like yourselves, something you may need to be reminded of: make mistakes. If you don’t, you’re not living. Or you’re certainly not living enough.

All of you remember from the introduction to philosophy that Descartes provoked a huge shift in how we think about ourselves. “Cogito ergo sum:” I think, therefore I am.

But, as the writer Kathryn Schultz has noted, seven centuries earlier, St. Augustine wrote something that, to her mind, is an even keener and more important insight: “Falor ergo sum.” I err, therefore I am.

Schultz makes this the focus of her fascinating book, Being Wrong: Making mistakes is what we do.

But we’re taught to deny our mistakes, we’re taught to pretend we didn’t make them or blame them on others.

Something I’ve learned in teaching and spending most of my life with art and artists is that art is particularly good about shining light on our mistakes. In a sense, that’s what art is for, what stories are about—showing us how people fail, showing us how what we need and what we love often come into conflict. Art is a good mirror for our human frailty. We can see our mistakes without being blamed for them.

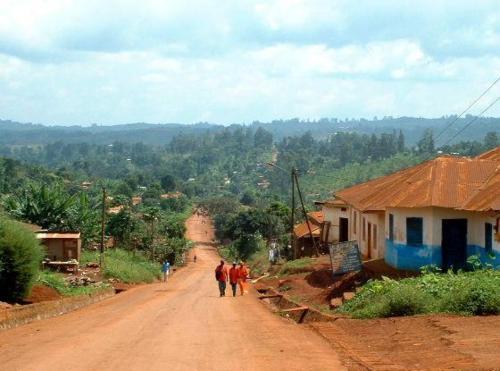

I love the story of the Fulbrighter who was actually the rare medical doctor in the program: a thoracic surgeon in Cameroon. He went around the countryside doing very essential surgery to help people with gangrene. His specialty was amputations. Often there was no hospital, sometimes there was no clinic. Occasionally, he did the surgery on the hood of his car. Someone asked him once whether or not he had malpractice insurance. And he said, “Of course I do. I have a ticket home.”

Fortunately, he never needed that insurance; he became renowned for his work. I’ll tell you, though, it’s a lot easier being a writer. It’s a good thing no one’s limbs are at stake in how often I get things wrong in poetry.

We have all gathered in a country of great poets. And I think that’s because Morocco is a country of great travelers. Not just the traditional nomadic past or the world migration of Moroccan Jews, but high-tech, 2012 global travelers. 10% of all Moroccans live abroad.

Moroccans love the talk of travelers. That talk is in their poetry, in the folklore, in the curiosity that greets strangers, in the quiet warmth in how Moroccans greet one another, how they travel in their talk through the hours of the day.

What I’m talking about is Darijah, the Maghreb dialect, the daily speech.

I don’t speak Darijah or any Arabic. But I’ve learned, as many of you already know, that it is Arabic mixed with Berber, French, Spanish, Portuguese and more recently German and English. It’s a process that all you linguists here know is called “code switching.”

Daily speech is all about switching between the words and expressions and habits of speech from one language to another. I’m fascinated by the way that the vast, traveling, cross-cultural Moroccan experience gets put together—in language.

And I’m interested in just how delicate the translation can be of making what is unspoken into something spoken, and then making what gets spoken into what gets written. And it’s ever-changing and accelerating. Darijah adds everything from Twitter to hip hop in its mash-up, in the hybrid of writing and speech.

But no matter how cotemporary it gets, Moroccan Arabic relies on a web of proverb and parable, small, compressed expressions of shared wisdom and tradition.

That is fascinating to me as a writer because it’s almost as if Darija embodies the Fulbright program’s values—a stirring together of differences in which all the original tastes remain the same. This is so beautifully described by another proverb: A jug can pour forth only what it contains.

Think of all that you contain. There is the Darijab of Fulbright—in your conversations, in your films and websites and poems and essays and blogposts and research.

The Navaho say that it takes a thousand voices to tell a single story.

You are the voices of the Fulbright. YOU are the Fulbright’s great story. Without you here to tell us what’s going on, we’d have no idea where to start.

And there is a Russian proverb that says: If you don’t know the trees you may be lost in the forest, but if you don’t know the stories you may be lost in life.

Your stories are maps to keep us from getting too lost in the complexities and troubles our big, interconnected world is facing.

But let me code-switch back to America. I was just in Atlanta and met with other Fulbrighters at another Enrichment Seminar in another darkened hotel ball room.

But of course I met some extraordinary people. And something one of them said struck me:

“You know, Fulbright is not about saving the world. It’s about sharing the world.”

Or in the words of a Moroccan proverb: In the desert of life, the wise person travels by caravan.

Or perhaps if we get a little closer to the research talk of this morning and measurable impact, there’s this proverb: One bee makes no swarm.

I want you to swarm with creativity. And leave behind some honey—some sweet success you have made by sharing your lives and your travels with others.

Speaking of travel:

You know, the great Beat writer Jack Kerouac would have been 90 today. He didn’t even make it to my age. But he certainly defined a way of American life.

As he wrote in the long scroll version of “On the Road, “ “There was nowhere to go but everywhere, so just keep on rolling under the stars.”

But is that the American way of life?

When I graduated from high school, 80% of Americans had drivers licenses. Now it’s dropped to 65%. Public transportation and a clean environment? Well, even American bike sales are down over the last decade. And the portion of Americans your age who still live at home with their parents has doubled.

All this sedentary life makes the huge popularity of video games like Grand Theft Auto a little ironic, doesn’t it?

As an editorial in the New York Times said, Generation Y has become Generation Why Bother.

Obviously, that’s not you. But I want to be sure that young Fulbrighters in your generation don’t become the Generation that Bothered Only Once.

I have been talking to a number of Fulbrighters who did their programs ten to 15 years ago and many have kept little or no touch with the countries they lived in. Most have not been back.

The percentage of ETAs who have International careers is small.

Perhaps social media will make this less likely. Perhaps though it will make our relationships even more fleeting.

Fleeting and departing—that brings up my last proverb—and this one is Yiddish: Some people are electrifying, they light up a room when they leave.